The Essay: Lady Gaga's "Disease" and the Perils of Creativity

The first single from Gaga's seventh album fits into her wide-ranging oeuvre by recalling her favorite themes to be explored in captivating, highly informed new ways.

Welcome back to Top Shelf, Low Brow. This is The Essay, where I take a long-form look at something major happening in culture. This time, it’s 3,000 words on Lady Gaga’s “Disease.” I’m sorry or you’re welcome.

Lady Gaga’s “Disease” is a strange song. Not just because it’s intentionally bizarre, a nod toward the dark pop roots that turned Gaga from a pop star into a superstar with The Fame Monster and Born This Way. (Though, that is a smart way to lure dissenters back into her grasp after forays into adult contemporary folk-pop and radio-friendly house music left longtime fans divided—more on that in a second). But “Disease” is unusual because it invites deeper analysis in ways that Gaga’s music hasn’t in some time.

With her last pop album, Chromatica, Gaga was penning vulnerable but decidedly straightforward lyrics about her battles with depression, chronic pain, and self-sabotage. Specificity in pop music can be a killer; it helps songs stand out from the crowd while ultimately alienating those who don’t have any intention of peering closer. (Sabrina Carpenter’s Short n’ Sweet was a wickedly clever LP that managed to walk that line with a heavy dose of old-school, winking humor that hopped between classic country punchlines and noughties-era acerbic jabs.) Lyrics like, “Every single day, yeah I dig a grave/Then I sit inside it wondering if I’ll behave” on “Replay” and “This is biological stasis, my mood’s shifting to manic places/Wish I laughed and kept the good friendships” on “911” are cutting and fascinating, but not necessarily difficult to parse. Chromatica is captivating, but not clever, and Gaga once staked her name on a penchant for cunning songwriting.

“Disease,” then, is a return to form in more ways than one. Here, Gaga is not only recalling the gloomy electronic music of her nascent days, she’s stripping down the songwriting too. The track’s structure is conventional but not tiresome. It lends itself to multiple listens with earworms scattered about the song, from its gnarly ad-libs that appear as screams and moans to a classically Gaga disyllabic “ah-ah!” that gets a few variations across its four-minute runtime. Lyrical precision takes a backseat to her signature wonky metaphors. Cockeyed imagery fits so neatly into the song that casual listeners may not even notice it. Others might say it’s her pathetic, poorly crafted attempt at reliving the glory days when her face—and all its different permutations—were inescapable. But with Gaga’s longevity in mind, one has to consider that nothing comes by mistake. And with the release of the single’s accompanying video, “Disease” takes an even more enthralling, knotted form that suggests Gaga knows exactly where she’s going: forward.

Among all of the off-kilter mixed metaphors in “Disease,” one line stands out as the most evocative. “I can smell your sickness,” Gaga sings in the penultimate bar of the song’s throbbing chorus. The lyric stands out for two reasons. First, it lands softly compared to some of the other lopsided analogies sprinkled throughout the track, particularly two that point toward religious salvation: “You reach out and no one’s there/Like a God without a prayer,” and, “If you were a sinner, I could make you believe.” What the hell is she implying here? Surely Lady Gaga, famously raised religious to the point where she’s had to work through it in several songs, knows that Gods don’t pray (Gods are prayed to) and sinners are also believers (it’s what makes them believe in sin).

We could chalk those lyrics up to Gaga building out the song with redolent thematic buzzwords, but let’s also consider the second reason that the aforementioned line about smelling someone’s sickness is so memorable. It implies that whoever Gaga is singing about has an illness so destructive that it’s noticeably rotting them, as well as a close proximity to this ailing figure. There’s an inferred intimacy between Gaga and her subject; they’re so close that she can detect the stench of their affliction. It’s the song’s most filthy and obscene line, the kind of thing you’d never say to someone you loved who was suffering and sick—unless you were referring to yourself.

I had been more than ready to attribute the lyrics in “Disease” to Gaga going for ideas that were brazenly dark but a little rote considering that she’s made several forays into this territory throughout her career. That assured confidence has been missing from her last two pop albums, Joanne and Chromatica, which had their rollouts consumed by her messaging. Joanne was written to heal her family’s lingering traumas, and Chromatica tried to funnel Gaga’s pain through a lens of bright resilience that is, unfortunately, too fragile to withstand the constant outpour of emotion from an artist. By Gaga’s own words, neither of those albums ultimately accomplished what they set out to do, but that failure is part of what makes them important within the scope of her career and each record’s broader meaning. Stripping down your sound and writing songs about your aunt won’t heal your family’s wounds, and escaping to a bright pink alien planet where sine waves are the currency is just an intergalactic way to run from your problems. You could hear Gaga’s distrust of her impulses in the music, too. The sounds were experimental for her career—and, to her credit, unlike anything her contemporaries were doing at the time—but the albums weren’t innovative in and of themselves.

“Disease” felt different from the jump. Perhaps it’s because it didn’t suffer from the weight of the “What will she do after ARTPOP?” question that plagued Joanne or a goddamn worldwide pandemic that still clouds even the fondest memories of its follow-up. But “Disease” is armed with the singular kind of conviction that a Gaga single hasn’t boasted in years. Its energy is immediate and relentless in the ways that “Just Dance,” Bad Romance,” and “Born This Way” were. With those three songs, it was as if there was a desperate need to write and release them gnashing at Gaga during her creative process. They weren’t burdened by industry pressure; you can hear that nerve embedded through each track. Hell, “Born This Way” was, according to Gaga, written in 10 minutes. (It sounds like it, too—take that how you will.)

When ARTPOP’s lead, “Applause,” was released in 2013, living up to the level of her own massive, worldwide, record-breaking success was already taking its toll. Gaga spoke openly about not being particularly enthused with the single selection process. “I never choose my singles, so I didn’t actually choose it,” she said of “Applause” in an interview on the Japanese edition of ARTPOP. In another chat with Ryan Seacrest, she said that the song was chosen as the lead by former chief of Interscope Records, Jimmy Iovine, who selected it after she played the album front to back. Though she already seemed disillusioned by that point, the perils of the ARTPOP era would end with her manager Troy Carter abruptly departing his post, and Iovine leaving Interscope. The changes put Gaga in flux for a few years as she navigated making and releasing music outside the headspace that left her career feebled. Though new management and a new label head would help her reorient, you can feel the restraint and uncertainty in the confines of Joanne and Chromatica. In both albums, there is something just out of reach, a personal passion missing from the core of the music. Even Gaga’s lauded work in film and television that came between ARTPOP and “Disease” felt more secure in itself.

So, what’s changed? In her Vogue cover story from last month, Gaga attributed part of this rekindled fire to her fiancé Michael Polansky, who said he saw that spark of creativity in her during the Chromatica Ball tour. (I echoed as much in my review of the concert special in May; there’s a fury running through her in the pop portions of that show that she hasn’t shown on stage since 2012.) “I encouraged her to lean into the joy of it,” Polansky told Vogue. And even if “Disease” is more sinister than anything Gaga has released in over a decade, it’s pulsing with total certitude, and not the kind that some pop stars have when they are simply recycling what worked at an earlier stage of their career. This time, I don’t sense that Gaga is writing for anyone else or to prove anything to herself—a sort of bloodhound talent that day-one Gaga fans have developed as we devour her expansive body of work and archive it among the catalog. She is simply creating from a place of desire and self-knowledge.

Just before the release of the “Disease” video, Gaga posted a message in an Instagram story that confirmed as much:

I think a lot about the relationship I have with my own inner demons. It’s never been easy for me to face how I get seduced by chaos and turmoil. It makes me feel claustrophobic.

Disease is about facing that fear, facing myself and my inner darkness, and realizing that sometimes I can’t win or escape the parts of myself that scare me. That I can try and run from them but they are still part of me and I can run and run but eventually I’ll meet that part of myself again, even if only for a moment.

Dancing, morphing, running, purging. Again and again, back with myself. This integration is ultimately beautiful to me because it’s mine and I’ve learned to handle it. I am the conductor of my own symphony. I am every actor in the plays that are my art and my life. No matter how scary the question, the answers are inside of me. Essential, inextricable parts of what makes me me. I save myself by keeping going. I am the whole me, I am strong, and I am up for the challenge. Happy Halloween.

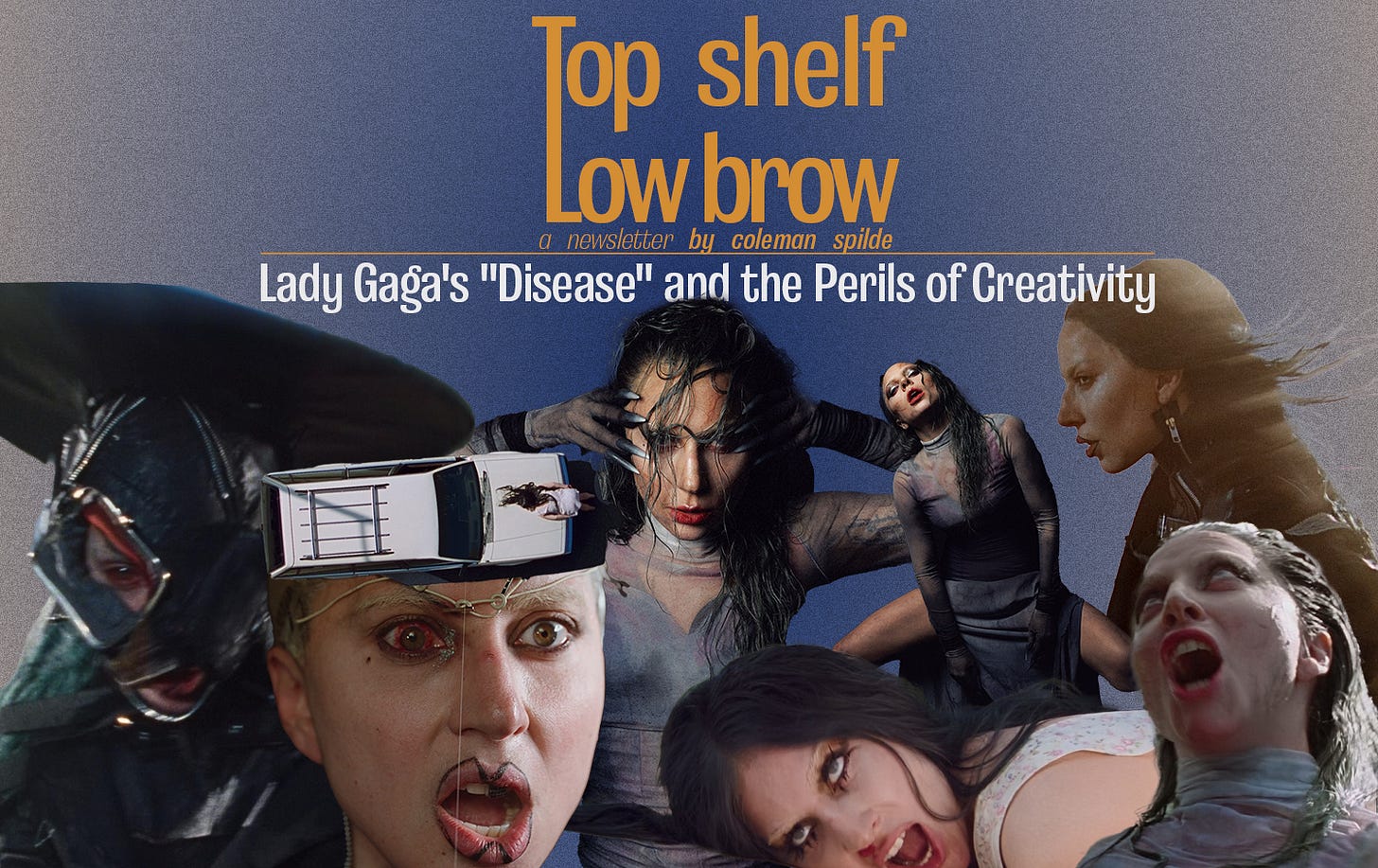

Thankfully for us, this makes the video easier to dissect without kneecapping its impact. “Disease” is Gaga’s best video in years, easily in the running for one of her greatest visuals. There are no protracted runtimes, no chintzy reveals that spoonfeed the meaning to the viewer. (Sorry, “911” video.) There is not one single iota of product placement shoehorned into the video, either. (Again, sorry “911” video, my dearest apologies “John Wayne” video.) And if the lack of brand deals and absurdly showy storylines didn’t already signal supreme confidence in her vision, consider this: There is no one in the video but Gaga. Sure, there are body doubles, but their purpose is to seamlessly mimic her. No costars, no dancers, no one to pull focus. “Disease” is entirely Lady Gaga, devoid of any other soul besides her own—a career first.

Six Gagas pursue and run from one another throughout the “Disease” video, seemingly controlled by one dressed entirely in black, right down to a leather gimp mask that only reveals one bloodshot eye. Let’s call her (or it) The Entity. In the video’s introductory sequence, this diabolical version of Gaga has just mowed down another Gaga with long black hair, who climbs the hood of the car that hit her, singing and swiping at the person behind the wheel in a shot-reverse shot. Shortly after, that black-haired version of Gaga is pulled from the car to wrestle with a strawberry-blonde Gaga in the street, and “Disease” cuts to its next sequence. Now, we find ourselves inside of room where two Gagas (each with black hair that’s sprouting blonde roots) battle it out. One hangs with her wrist handcuffed to a pole above her while the other moves about freely, but both are locked in a death match, observed by The Entity, a creature ruling over their fate.

In the video’s final stretch, the shadowy being governing the destruction of these different Gagas births a new copy, sporting grey hair—let’s conveniently work in a bit of color theory and say that’s a mixture of blonde and black tones. This new Gaga looks up at her maker from a puddle of black amniotic ooze and senses a childlike familiarity toward her. Grey Gaga takes The Entity’s hand and accepts comfort and safety in her embrace. But when the progenitor takes off her mask, the child screams in terror and flees, only to be trapped by the closing walls of a nearby home. (As a brief aside, from that scream of horrific recognition, I see both Laura Palmer’s scream in Twin Peaks: The Return and Léa Seydoux in the final scene of Bertrand Bonello’s The Beast. It’s a full-bodied expression of horror that comes only when you realize you’re trapped in an endless cycle of darkness. Also, “Disease” has Unedited Footage of a Bear written all over it, but I digress.)

From Gaga’s sentiments about the video, we understand that “Disease” is all about being relentlessly pursued by your self-destructive tendencies. She’s worked through this theme before—the very literal takeaway from “911” is “my biggest enemy is me”—but never in a way that has been so resonant. She discusses morphing between selves and the seduction of destruction. I feel intimately familiar with the kind of temptation she’s talking about. As an artist of any kind, when you create work that is touching and special but born out of a place of true suffering, that strife becomes an elixir that you want to consume over and over again. Our brains are malleable enough to become addicted to the pain, especially when we’re praised for the work it begets.

In her 2013 performance of an art piece called “Flying”—part of her collaboration with Robert Wilson—Gaga hung upside down in bondage for 45 minutes as a tribute to her late friend Alexander McQueen. “That’s part of my existential crisis as an artist, that I felt compelled to do it,” Gaga said about “Flying” in 2021. She felt called to make art that demanded she suffer, if only as a means to honor someone else’s pain. You can trap yourself in this kind of artistry, doomed to bear your own ruinous cruelty so that you might create something extraordinary again. We convince ourselves that emotional rapture and boundless, dangerous passion are the creative tools for any artist, and even when we learn to accept that those flames will burn us, their warmth is enchanting. It takes a long time to understand that there is no use in running. The Entity will catch up with us eventually. But by acknowledging this cycle, Gaga has kept the flame at a safe distance, making her most fascinating work in years by examining the fire instead of plunging into it.

Gaga’s own words about the video are the most moving, so I won’t try to extricate any further meaning about its message beyond what I already have. Rather, I want to examine what I think is one of the most interesting facets of the video that I haven’t seen anyone mention: You can’t tell which of these Gagas is “good.” There are, of course, context clues and the implication that The Entity is the one with the dastardly plans. But maybe the way she’s dressed isn’t meant to convey that The Entity is evil, maybe she’s simply a combat-ready wrangler of sorts. Perhaps it’s dark-haired Gaga and all of the other clones that The Entity pursues who are sowing Gaga’s inner turmoil. Just as much as she represents the chaos that follows Gaga, The Entity could epitomize an emboldened, strong-willed Gaga who knows how to tame the versions of herself who wish to cause her harm. These clones are birthed from the one true Gaga, fleeing when they recognize her or taunting her with their immortality on the hood of The Entity’s car. She wants to kill them because she can smell their sickness. She is a mother who can feel her child’s pain, and wants to rid the world of these destructive copies that bear her likeness.

Then, it could be flipped, explained in the way that most would see it: with The Entity as an evil figure. But that there’s any space at all for narrative inference is a major sign that we’re dealing with the same Gaga whose immense, strange, and sometimes preposterous ideas brightened a once dulled pop music universe in the first few years of her career. She used to speak at length about multiple interpretations of her art, often adding new lines about its meaning in different interviews during the extensive promotional cycles for Born This Way and ARTPOP. Broader analysis has been something that Gaga’s output wasn’t welcoming for years. What the public got was what we got, and any video was merely a celebration of the music, an extension of what the song already told us. For an artist whose videos and visuals we could once rely on to enhance a song’s meaning, those years felt far less Gaga.

But like any great artist, the creative dips are important too. When art doesn’t quite connect the artist with their audience the way that either party hopes it will, failure makes any wins that follow all the more enjoyable. As much as she is a pop star, I see Gaga’s artistry in the same way I see that of great film directors. She’s moving through different, wide-ranging ideas that use her stylistic signatures to explore a core set of themes that interest her. Her work is all connected, rather than each album being a full reinvention. Perhaps Gaga is realizing that she doesn’t want to—and really, doesn’t need to—be beholden to the archaic idea of “reinvention” that so often plagued Madonna and Gaga’s other contemporaries. What if Gaga has more to say on a subject she’s already explored in the past? And what if she can do that in new, fascinating ways that she hasn’t done before? There’s no shame in looking back while you move forward. If anything, that’s the only way to make sure you stay one step ahead of whatever’s chasing you.

Your essay is beautifully written. All the things i felt and didn’t know how to articulate are here in your work. I specifically googled a review of this song in hopes to find a constructive critique and you nailed it. Brava!